In an early analysis of the source of material for the Book of Ether, we get the sense that this book is the product of a long history, including several stages of composition, beginning with Jared, after whom the Jaredites were named.

First, there would have existed among the Jaredites general oral traditions and some specific archaic writings. Anciently, the basic historical information found in the book of Ether was probably handed down in the form of a king list kept among the descendants of Jared, who were the Jaredite rulers for over one thousand years.

This king list could have been either written or oral. King lists similar to the one in Ether 1 appear among the earliest written records in ancient Mesopotamia, and many Mesoamerican monuments have now been shown to contain historical information about royal lines. Most of the short accounts of each king’s reign in Ether 6–11 are not dissimilar in scale. Yet some early peoples also orally transmitted memorized king lists and stories about their origins. While it is not clear whether Ether worked in this respect from a written royal record, an oral tradition, or a combination of both, the integrity of the Jaredite king list as a separate source is underscored by its apparent insertion as a unit in the midst of Moroni’s introductory materials (Ether 1:3–5, 33). The words in these verses follow very closely the words of Mosiah2 in Mosiah 28:17. The king list appears in the middle of this material, from Ether 1:5, which mentions that the account begins “from the tower,” to verse 33, which picks back up with the same language: “from the great tower.”

The genealogy in the book of Ether (Ether 1:6–33) is a prime example of these ancient king lists. The list, which served as an identification and reference for the author, is listed from the author down to his earliest ancestor. Ether is named first, Aaron is tenth, Shiz is twentieth, and Jared is thirtieth. Whether or not the number thirty is important is not clear, but the Maori people can recite their lineage, and it was important to them to be able to recite their lineage back thirty generations.

Likewise, the Jaredite king list given to us by Ether contains thirty generations. Here is that list as it was given in Ether 1:6–32, from the perspective of Ether, the narrator and the final Jaredite prophet.

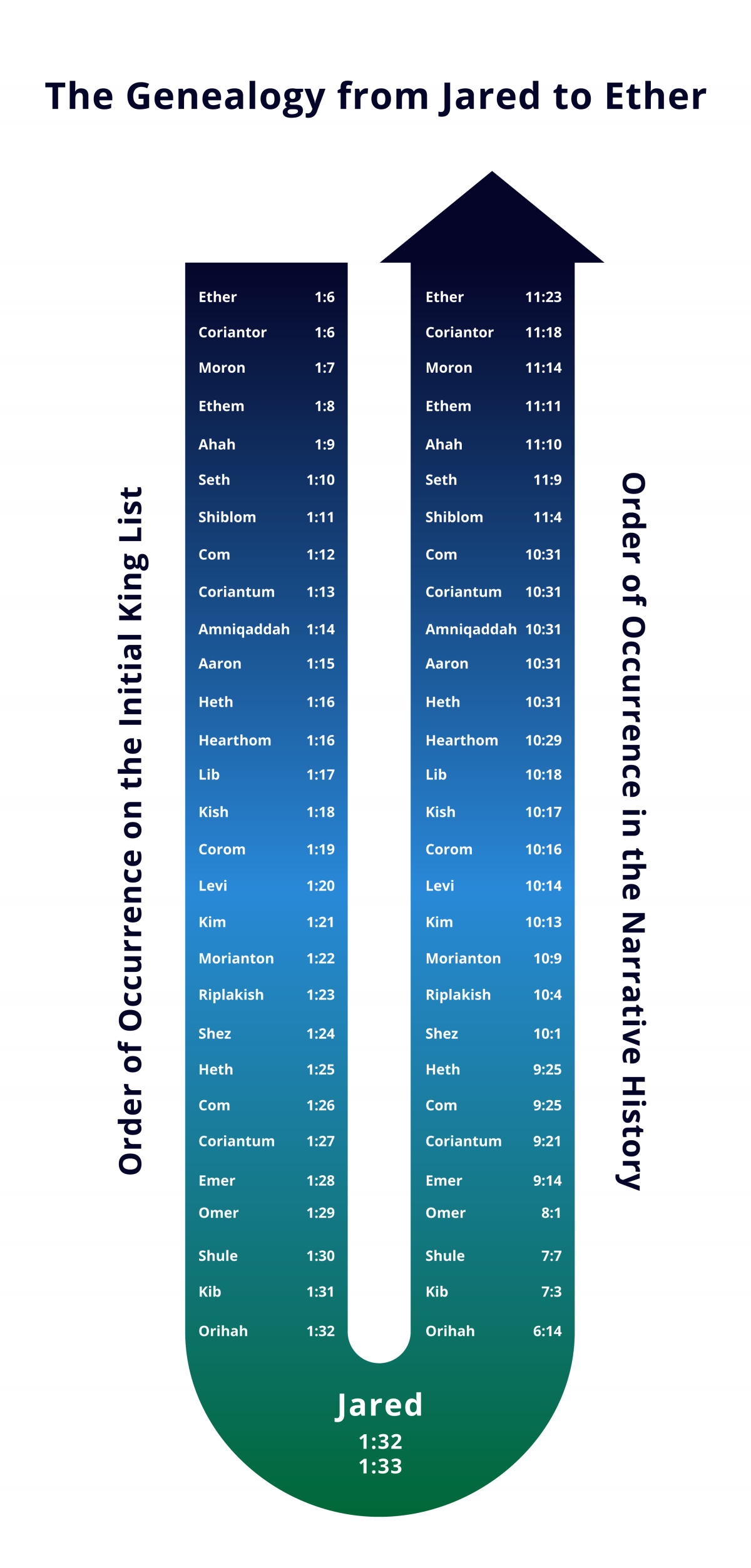

Notice that the names are first listed from Ether back to Jared, in genealogical order:

Order | Passage | Name |

1 | 1:6 | Ether, the son of |

2 | 1:6 | Coriantor, son of |

3 | 1:7 | Moron, the son of |

4 | 1:8 | Ethem |

5 | 1:9 | Ahah |

6 | 1:10 | Seth |

7 | 1:11 | Shiblom |

8 | 1:12 | Com |

9 | 1:13 | Coriantum |

10 | 1:14 | Amnigaddah |

11 | 1:15 | Aaron |

12 | 1:16 | Heth |

13 | 1:16 | Hearthom |

14 | 1:17 | Lib |

15 | 1:18 | Kish |

16 | 1:19 | Corom |

17 | 1:20 | Levi |

18 | 1:21 | Kim |

19 | 1:22 | Morianton |

20 | 1:23 | Riplakish |

21 | 1:24 | Shez |

22 | 1:25 | Heth |

23 | 1:26 | Com |

24 | 1:27 | Coriantum |

25 | 1:28 | Emer |

26 | 1:29 | Omer |

27 | 1:30 | Shule |

28 | 1:31 | Kib |

29 | 1:32 | Orihah, the son of |

30 | 1:32 | Jared |

Then, as the story of the Jaredites unfolds, the same names are given in exactly the opposite order, in their historical order from Jared down to Ether. Here are all of those same names in the order of their first mention in the scriptural narrative, with their chapter and verse numbers given:

Order | Passage | Name |

1 | 1:33 | Jared, begat |

2 | 6:14 | Orihah, begat |

3 | 7:3 | Kib, begat |

4 | 7:7 | Shule |

5 | 8:1 | Omer |

6 | 9:14 | Emer |

7 | 9:21 | Coriantum |

8 | 9:25 | Com |

9 | 9:25 | Heth |

10 | 10:1 | Shez |

11 | 10:4 | Riplakish |

12 | 10:9 | Morianton |

13 | 10:13 | Kim |

14 | 10:14 | Levi |

15 | 10:16 | Corom |

16 | 10:17 | Kish |

17 | 10:18 | Lib |

18 | 10:29 | Hearthom |

19 | 10:31 | Heth |

20 | 10:31 | Aaron |

21 | 10:31 | Amnigaddah |

22 | 10:31 | Coriantum |

23 | 10:31 | Com |

24 | 11:4 | Shiblom |

25 | 11:9 | Seth |

26 | 11:10 | Ahah |

27 | 11:11 | Ethem |

28 | 11:14 | Moron |

29 | 11:18 | Coriantor |

30 | 11:23 | Ether |

The following graphic combines these two sequences visually into a single graphic:

Two of the more uplifting features of the book of Ether are the accounts of the tremendous faith of Jared and, even more so, of the Brother of Jared, who were the first characters in what may be considered Ether’s family history. Note that Ether did not descend from the brother of Jared. Rather, he descended from Jared, and so the brother of Jared is not mentioned in the genealogical king list in Ether 1, though he was crucially important.

Culturally, king lists were especially important in ancient Mesopotamia, the place where the story of the Jaredites begins. In Mesopotamia, the number system was based, not on the number 10, but on the number 60. Throughout the ancient Near East, for commercial and legal purposes, there were 60 shekels in a mina, and 60 minas equaled 1 talent. The number 60 was conveniently divisible by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 15, 20, and 30. And thus, the number 30, being the number of names in this king, list may well have had some cultural meaning or symbolic significance.

The written history that is then given in the book of Ether follows this list chronologically, but now in the opposite order, beginning with Ether’s oldest ancestor whose name shows up last on the list and working down to the time of Ether, whose name is first on the list. Other names appear in the history that are not listed in this royal lineage (the brother of Jared, for example), and sometimes the names of these kings appear in the narrative history more than once, but none of the names in the king list appear their first time in the narrative out of this order. Thus, the thirty names first given from Ether back to Jared are then introduced into the narrative from Jared down to Ether in exactly the opposite order, and not a single one of them is left out.

Needless to say, the precision of the reverse repetition of the Jaredite king list in the book of Ether is absolutely amazing. If you haven’t seen this before, join the crowd. I first saw this feature in the book of Ether in 2009.

Also, in this context, think of Joseph Smith dictating the translation of Ether 1–12 to Oliver Cowdery, presumptively over the four days from May 25–28, 1829. Imagine anyone telling a story, beginning with a list of 30 names, and then over the next four days elaborating the histories of those 30 leaders in exactly the opposite order, interspersing various side stories, interactions between parties, conflicts, and editorial asides, and yet never leaving out a single name in the original list or confusing their order. There is no evidence or reason to believe that Joseph had any notes or even access to Oliver’s manuscript page for Ether 1 as he revealed the text of Ether 6–12. In fact, reported interviews from Emma Smith and David Whitmer indicate that there were no such outlines or notes.

Thus, in addition to Moroni’s divinely guided work in remembering, abridging, and writing the book of Ether, we benefit from the inspiration of Joseph Smith, who translated this record accurately and precisely “by the gift and power of God.”

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Book of Ether Begin with Such a Long Genealogy? (Ether 1:18),” KnoWhy 235 (November 21, 2016). “It may be easy to think of the authors of the Book of Mormon as distant from readers today. They’re people from the remote past, who may seem difficult to relate to in modern times. Yet, on occasion, the curtain gets pulled back and the modern reader can almost sit with the authors and compilers and observe their manners and methods as they work. The book of Ether is one of those occasions. One can almost see Ether referring to the king list as he crafted his 24-gold-plate record of the Jaredites. One can also observe Moroni as he interspersed his own editorial commentaries (Ether 1:1–6; 3:17–20; 4:1–6:1; 8:18–26; 12:6–41) into the Jaredite story as it unfolded.” See also, John W. Welch, “Preliminary Comments on the Sources behind the Book of Ether,” Preliminary Reports (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1986). On the timing of the translation, see John W. Welch, “Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon: ‘Days [and Hours] Never to Be Forgotten’,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2018): 10–50.

John L. Sorenson, “The Years of the Jaredites,” Preliminary Reports (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1969).

Thorkild Jacobsen, “The Sumerian King List,” Oriental Institute Assyriological Studies 11 (Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute, 1939); S. N. Kramer, The Sumerians (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1963), 328–331; A. Malamat, “King Lists of the Old Babylonian Period and Biblical Genealogies,” JAOS 88 (1968): 163–173.

Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, “Mayan Linguistics: Where are We Now?” Annual Review of Anthropology 14 (1985): 193.

M. D. Johnson, The Purpose of the Biblical Genealogies, with Special Reference to the Setting of the Genealogies of Jesus (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 101, 115.